I didn’t receive my autism diagnosis as a child. It’s something I blog about often, usually whilst remarking on society’s trend to let autistic girls languish in silence for years. As an undiagnosed autistic child, I lost most of my childhood and adolescence to a silent and impenetrable hell.

On the surface, I presented as bright, outgoing, intelligent. I was called “an old soul,” “wise beyond my years,” and I took that praise to heart,” drifting deeper and deeper within myself until I dared not allow myself any feelings at all. I didn’t know how to act like other kids and I was so confused by the differences between myself and my peers that I lapped up any praise which suggested that my differences might be positive.

Because, without an explanation for how my brain worked, I assumed that I was the problem. Internally, I labelled myself “broken” and “bad” because whenever I read about people who— like me— didn’t fit in, didn’t feel like other people, they were always criminals and serial killers. As a child, I connected those dots and spent years assuming I must have some hidden streak of deviance that I must suppress at all costs. After all, I assumed, why else would I feel so different?

As a 25-year-old with 5 graduate degrees, a thriving social life, and— crucially— an autism diagnosis, I have shed many tears for the undiagnosed little girl I used to be. On good days, I want to hug her and whisper that she isn’t the problem, that there’s a name for what’s going on in her head, and that none of this is her fault.

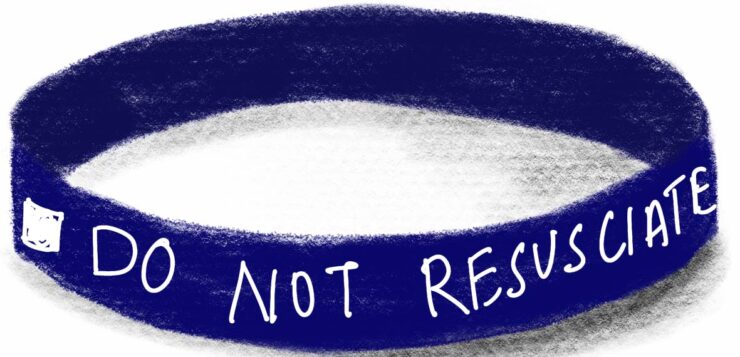

But on the hardest days, I’m angry. I mourn the unfettered happiness I could have had. I grieve the unfractured sense of self I could have cherished. I imagine how much happier I could have been if I was diagnosed with autism as a child. …that was, until I read an article with this title: “Children With Autism Were Offered ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ Orders During The Pandemic.”

Not only has this story been the subject of reports from multiple papers, an investigation by the Daily Telegraph revealed that “shocked parents are now worried their child could have agreed to the order because they may have not ‘understood the question.’”

Further reading shows that this question was frequently raised to teenagers with autism and Down Syndrome— 18-year-olds who, just like me at 18, would be legally capable of making their own medical decisions, but functionally vulnerable. Would I have understood that question at 18? Would I have realised that I was legally signing my life away, agreeing that my life didn’t matter? Almost definitely not.

And therein lies the problem. I was— if you want to call it that— “lucky” enough to present as neurotypical through my entire childhood. The masking that destroyed my self-worth, my identity, and my inner life enabled me to be labelled “normal.” So, because I was not diagnosed as a child, I would not have been on a list of “people this option should be offered to.” And when I’ve discussed headlines like these with my GP, with my therapist, I’ve received a resounding, “But these headlines are never about YOU!”

Although these statements are made to reassure me, they have the opposite effect. Because these phrases reinforce the assumption of a ‘compliment’ I consistently receive— the pseudo-complimentary, “But you don’t LOOK autistic!” While intended as a positive thing, this phrase infuriates me because it tells me one crucial thing: that people mean it as a compliment because they’re saying I don’t look strange or different to them.

Behind the seemingly innocent phrase “you don’t look autistic” is the belief that it’s okay to discriminate against people who do. And, from there, it’s not a big leap to assume that it’s okay to suggest DNR orders to children who DO look autistic, because ‘their lives matter less.’

But it’s not okay to pick and choose the lives that matter. It’s not okay to ‘compliment’ me on ‘not looking autistic’ and also feign outrage over this headline. And it’s especially not okay to say that my (autistic) life matters but another autistic person’s doesn’t.

When I’ve discussed this headline with others, some people have attempted to justify their position to me by saying that because I am a successful student who has won awards and scholarships, my autistic life holds more value. That no one would ever think I should be offered a DNR order. Thus, the message is loud and clear: my life has value because I “contribute to society.” Because I’m capable of doing or producing something that other people value.

But that logic is exactly what terrifies me. All autistic lives have value— full stop. Our contributions to society— or lack thereof— does not give anyone the right to play God or to sneakily institute a return to the eugenics movement. And make no mistake: that’s exactly what this DNR order is.